published by Ashley Reese1, Kevin Yee2, Michael Preston3 | July 2021

1,2 University of South Florida 3 Florida Consortium of Metropolitan Research Universities

Abstract

In March of 2020, the global COVID-19 pandemic forced almost all-American universities to shift to online modalities for teaching and instruction, including STEM Labs. While the delivery of online labs is not a new concept, the scale and speed at which universities moved traditional campus-bound lab activities created challenges few anticipated. At the same time, students were asked to adjust their learning style to an online environment, instructors of record were also requested to modify courses designed for in-person instruction. This paper narrates a case study of three large metropolitan research universities in Florida and their efforts to collaborate to create learning environments that ensured safety, elevated learning, and supported students. The collaborative effort focused on exchanging best practices, course-specific curriculum exchanges, and peer-supported environments to pose questions and scenarios. Results demonstrate that when faculty and staff collaborate, no matter the discipline, they reduce barriers to teaching and learning. The authors discuss the history, techniques, and planning of this collaboration, including resulting accomplishments.

Keywords: online learning, STEM, higher education collaboration, laboratory, curriculum development

Introduction

This is a case study and narrative about how three Metropolitan Universities in Florida, Florida International University, University of Central Florida, and the University of South Florida, collaborated to move their STEM Labs during the pandemic to remote learning and to find and share resources and best strategies. In sharing how we initiated communication and what we learned from working with other higher education institutions, this article hopes to narrate how universities might establish similar communication lines and collaboration between colleges and universities. While many universities have stories about switching to the remote teaching environment, there is a unique story in how these three institutions came together and how these efforts helped half the students attending college in Florida.

The Florida Consortium of Metropolitan Research Universities emerged from a shared commitment to transforming students’ lives and the metropolitan areas that we serve at FIU in Miami, the UCF in Orlando, and USF in Tampa Bay. Together our three institutions share:

1) Common values of serving our student bodies and promoting success in and beyond the classroom for students of all backgrounds, no matter what socioeconomic status.

2) Strengths as public research universities that also have earned the Carnegie Classifications of Community Engagement for Curricular Engagement, and Outreach and Partnerships; and

3) A preference for collaborative work to improve the lives and livelihoods of Florida’s next‐generation workforce and leaders.

The combination of resources, expertise, and commitment will allow the Consortium to launch and complete initiatives at a speed and scale that none of the universities could attain separately. Each university has independently launched student success initiatives that have already improved college completion rates. By integrating their efforts in a meaningful way, the three institutions intend to accelerate the pace and extent of change at their institutions and communities by sharing. learning, and applying best practices, policies, and program designs. Florida Consortium members hope to produce more career-ready graduates with lower debt, better training, and adaptable skill sets. The Consortium will drive the economic development of Florida by creating synergies and efficiencies between the state’s three large metropolitan public research universities and the public, private, and non-profit sector institutions that rely on them for a steady and growing supply of talented graduates.

An Established Relationship

The Florida Consortium of Metropolitan Research Universities is comprised of FIU, UCF, and USF. Founded in 2014, the combined universities account for about 48% of the State University System of Florida undergraduate enrollment. In June 2015, the Consortium received a $506,925 grant from The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust (2016). The resulting project focused efforts on increasing the number of higher education graduates who also have developed the skills and abilities in the STEM fields to meet the growing Florida economy (Preston, 2017). This grant required the Florida Consortium to convene STEM faculty to work under Network Improvement Communities regularly. These NICs facilitated the grant’s work and allowed faculty from all three universities to interact and develop a professional relationship.

Through these regular convenings of mainly STEM faculty, community-developed across the three institutions. The participants now had contacts – including names and faces – at participant campuses, which meant that faculty formed networks outside of their institutions to ask questions and share resources when challenges arose. This relationship was different from an informal conference because the NICs were required to produce and report findings based on their collaborative work.

The collaborative nature of the relationships formed resulted in a much better communication stream once the member institutions decided to create an online labs workgroup. Traditionally, one of the difficulties of reaching for peer assistance when a pedagogical or logistical issue arises is the lack of consistent response. Many faculty have had the experience of sending out a survey – perhaps across institutions or even nationally only to receive only a small percentage of replies. Survey responses can vary widely from 84.4% (Saleh, Amany; & Bista, 2017) to 12.4% (Crouch, Robinson, & Pitts, 2011).

When faculty go beyond institutional borders, they establish a working or research relationship. Collaboration leads to familiarity that transcends typical modalities of communication and contact. The request is not impersonal but rather personal and has the validity of the unique relationship to acknowledge priority. This group has helped each other in the past and will continue to help one another in the future. For this reason, when Florida Consortium universities switched to remote learning, the member universities turned to one another for resources, confident that together the group could solve the pedagogical problems that had arisen due to the pandemic.

Identifying the Problem

With the rapid move to remote learning in the spring of 2020, there was concern about conducting labs safely and with a high degree of academic rigor amongst STEM faculty. The members of the Florida Consortium were not alone in trying to solve this problem. For example, Heather R. Taft from Colorado State University Global published in The Chronicle of Higher Education strategies to move their labs to the online environment (Taft, 2020). Sharing resources, particularly for something as challenging as offering science labs to students at home, became paramount.

For this reason, in April 2020, Dr. Paul Dosal, the Vice President for Student Success at USF, reached out to Dr. Kevin Yee, director of USF’s teaching center, the Academy for Teaching and Learning Excellence (ATLE). Knowing USF’s established relationship through the Florida Consortium, Dr. Dosal, asked that USF reach out to the colleagues at UCF and FIU for resources. This request led to creating a pedagogical survey was sent to STEM faculty at FIU, UCF, and USF.

How to Reach Out

The eight-question survey asked participants to share their personal information, such as their names, email addresses, and current university. They were asked to choose one of six disciplines they taught: Biology, Chemistry, Engineering / Computer Science, Geography / Earth Sciences, Math / Statistics, and Physics. They also were asked to fill in the subject and course number for the applicable labs. This information was used to connect faculty with similar disciplines and like concerns to work closer in smaller groups if the situation called for it.

Survey questions asked participants to share:

- “What workarounds, tools, apps, or processes were successes in your switch to Remote and Online content delivery? (Note: the examples can be very specific to your discipline.).”

- “What hurdles or challenges have you not solved yet? (Note: the examples can be very specific to your discipline.).”

There were sixty-six respondents to the survey. The survey was emailed to 1,219 STEM faculty across the Consortium, including 380 at FIU, 439 at UCF, and 400 at USF. As part of the incentive, ATLE shared the responses amongst colleagues as a detailed resource.

What We Found / Results

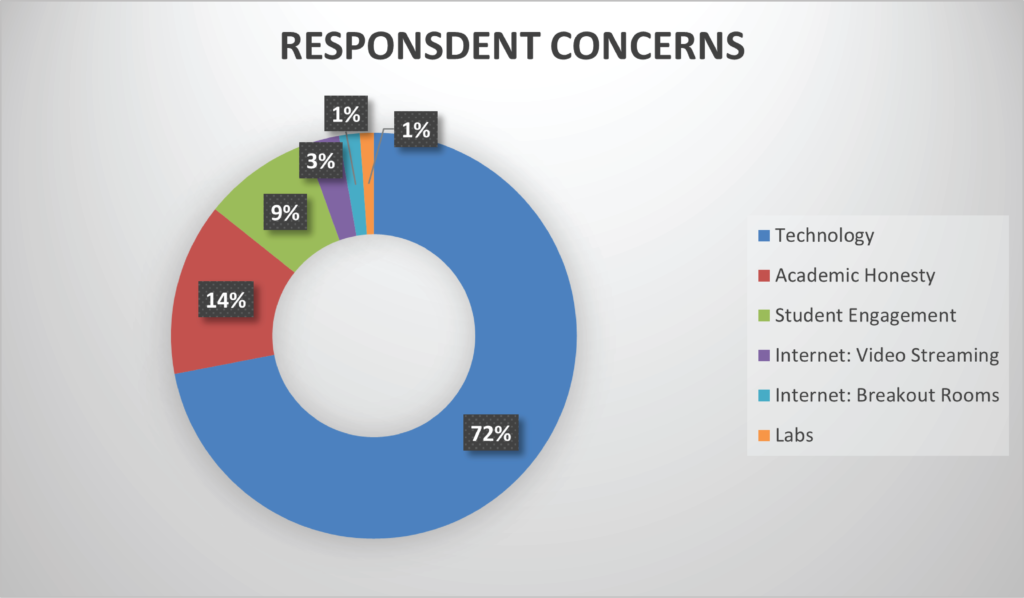

The responses to current hurdles do not focus on the lecture / class-delivery tools and the difficulty in engaging students through those tools—the lack of a consistent interpersonal contract with a new experience for many faculty. Sixteen responses shared concerns about how to increase student engagement and interaction with each other and the instructor. Regarding the lecture or video tools themselves, the problem was more about internet connection not supporting video streaming (5 responses) or the challenges of setting up breakout rooms (3 responses).

One of the concerns the Florida Consortium had for STEM faculty was moving from in-person labs to the virtual space. While eight responses mentioned labs in their workarounds, only two responses cited labs as a hurdle. It appeared that, for the most part, faculty had found ways to incorporate labs virtually, and the technology and kits were available to complete this task. The 66 respondents provided a representative sample of faculty who have solved some of their major online lab concerns and were ready to share resources with other STEM faculty across the Florida Consortium.

Many of the hurdles identified by faculty were related to exams and cheating. Of the 66 individual responses, there were 25 mentions of academic honesty in the remote environment. Some expressed worry that the tool Proctorio, meant to capture students’ behaviors during exams, is unreliable (eight responses), and three respondents stated they do not use the tool. Similarly, three responses are looking for strategies to write better questions to avoid plagiarism.

Most of the focus in responses was on Technology issues. In the 66 individual responses, the faculty mentioned technology 131 times.

Once they identified their hurdles, one survey goal was for faculty to find some possible solutions in their peers’ workarounds. 12 responses to the workaround question mentioned;

- Introducing strategies for exams, including giving open-ended questions instead of multiple-choice.

- Posting a warning about plagiarism.

- Having undergraduate learning assistants serve as proctors in Zoom breakout rooms,

- Replacing high-stakes exams with frequent low-stakes, multiple-attempt quizzes.

One respondent replaced the final exam with a final project instead. These strategies speak to pedagogy more than technology. Only four workaround responses mention Procotrio or online proctoring tools.

Additionally, because these survey results emphasized the concern of academic integrity in the remote environment, USF hosted the Southeast International Center for Academic Integrity conference in November 2020. This conference took on the focus of academic integrity in COVID-19 (Reese, 2020). Faculty, administrators, and students from across the southeast United States, including those in the Florida Consortium, met to discuss strategies to prevent students from cheating when classes are remote. This conference directly addressed many of the hurdles identified in the initial survey.

These survey results show a glimpse into what STEM faculty across three Florida public universities were doing to adapt to the remote environment. Florida Consortium faculty rose to the occasion in the Spring of 2020 and continued their work for an entire academic cycle despite the challenges of COVID-19. Faculty have continued to strive to provide quality education to students, all while learning new technology, new ways of teaching and assessing, in addition to coping with the challenges presented by a pandemic.

What We Would Do Differently

The effectiveness of these efforts is unknown beyond the few anecdotal emails we received thanking us for these resources. Part of this was intentional, as we recognized the burden faculty had by their efforts to move their courses to the remote environment while simultaneously coping with the additional personal stressors brought on in a pandemic. Perhaps we might ask for follow-up feedback in the future, but we cannot imagine asking for (and willingly receiving) input in this scenario.

Our efforts to gather and disseminate information were most likely not unique across the three campuses. Because of the rapid nature of adapting to be remote, the three campuses could not synchronize the communication and efforts to move to the online environment. There might already have been efforts underway from other groups to harvest this information by talking to faculty. For this reason, one of the changes we would make in the future would be more of a unified approach – reaching out first to bodies who might be interested in conducting this research, in part to reduce survey fatigue for faculty and to increase participation and therefore, resources potentially.

Finally, our survey was emailed out to the faculty directly. While there was buy-in for submitting their responses because these faculty would then receive their colleagues’ results, we also relied on the fact faculty would know about the Consortium and feel comfortable sharing their results with us. In the future, emailing chairs across the campuses and asking them to forward the survey to their faculty might have increased the number of responses. Of course, this attempt comes with a similar caveat that chairs and faculty are incredibly busy. In these unprecedented times, asking more of those already working so hard in higher education came with hesitation.

Conclusion

While the need for extending online labs as a necessary avenue for conducting all classes seems to have waned as the pandemic has slowly started to subside, there is a lesson to be learned. When faculty collaborates in a short amount of time and utilizes Network Improvement Committees, it forms trusting relationships. Collaborative networks can help us scale and work at a speed generally not seen in academia. There is also a wisdom of crowds approach taken. As faculty offered advice and then supported others’ solutions, there was a sense that if it worked at FIU and UCF, it must work at USF and vice versa. It also models the kind of academic work we expect from our students. Faculty present themselves as working in groups and achieving results aligns with many of our university learning outcomes. This collaborative model will be modified in the future to accommodate lessons learned and to bring faculty together in different disciplines. There is an expectation that online learning will continue to expand as students see the value in course flexibility and delivery methods.

References

Crouch, S., & Robinson, K. (2011). A comparison of general practitioner response relates to electronic and postal surveys in the setting of the National STI Prevention Program. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00687.x.

Saleh, A., & Bista, K. (2017). Examining Factors Impacting Online Survey Response Rates in Educational Research: Perceptions of Graduate Students. Journal of Multidisciplinary Evaluation. https://journals.sfu.ca/jmde/index.php/jmde_1/article/view/487.

Taft, H. R. (2020, July 23). How to Quickly (and Safely) Move a Lab Course Online. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-to-quickly-and-safely-move-a-lab-course-online/.

University Of Central Florida Foundation Inc. Helmsley Charitable Trust. (n.d.). https://helmsleytrust.org/grants/university-of-central-florida-foundation-inc-2/.